Published in English translation as an appendix in E. Milhaud, ORGANISED COMPENSATORY TRADING

Williams and Norgate Ltd, London, 1937

A WAY OUT OF THE MONETARY CHAOS.

By Dr Walter Zander

The subjoined study is the outcome of a lecture delivered by the author on 8 March 1935 before the National Institute of

Geneva (Institut National Genevois).

The devaluation of the belga, which supervened in April 1935, is taken account of here. On the other hand, the May 1935 crisis

of the French franc took place after this study had gone to press. It forms an additional link in the lengthening chain of monetary

difficulties and offers one more illustration of the dangers to which every monetary system, even when supported by an enormous

gold reserve, is exposed under the rule of a forced rate for the notes of central banks. The proposals so far made known for ending

the French monetary crisis do not suggest anything beyond what is implicit in the views generally current to-day.

Berlin, 2 June 1935.

Dr. Walter ZANDER.

1. The Monetary Chaos.

The States participating to-day in the world economy

may roughly be said to be divided into two groups. One of

these has abandoned the gold standard and has thus removed

the foundations of its currency. The other has introduced

foreign exchange legislation and has thereby abolished the

freedom of settlement operations. The first group includes

more particularly England, the sterling bloc countries, the

United States, and Japan; the second group, Austria,

Germany, Russia and the great majority of the remaining

countries. Placed between these two groups, is the steadily

disintegrating gold bloc. Italy left it for all intents only

recently and yesterday as it were Belgium followed suit. If

we bear in mind that since the War France and Poland had

already devaluated their currencies to a fraction of their pre-

war parity, virtually Holland and Switzerland alone may be

said to uphold the pre-war monetary system. However, even

in these two small countries, which represent but a tiny

fraction of the world economy, certain restrictions

concerning the convertibility of banknotes and the gold

market have been introduced, and the general uncertainty as

to the future of currencies exerts a baleful influence in these

countries also.

2. Disadvantages of Devaluation.

Whether the abandonment of the gold standard is

advantageous to an economy, is decidedly problematic. In

most cases the object aimed at has not been attained. So far

as devaluation is intended to stimulate exports, we should not

forget that for most countries the magnitude of their export

:trade compared to that of their total trade is comparatively

insignificant. This alone renders it questionable to embark,

for the sake of the export trade, on measures which modify

the basis of a national economy as a whole. Moreover, such

measures, if successful, may be imitated by any other

country, thus nullifying their favourable effect. Accordingly,

the abandonment of the gold standard has led to "a race for

the worst currency", in which the most powerful States are

participating. It is obvious that in the long run such measures

for the stimulation of the export trade are bound to prove

worthless.

Moreover, devaluation does not only affect the export

trade of a country. On the contrary, it touches every branch

of an economy. This holds most especially of imports, since

these must become dearer to the precise extent that exports

become cheaper. So far as exporting, like in Germany for

example, presupposes the importing of raw materials, a

portion of the anticipated gain is thus necessarily lost. But, in

general, import restrictions, so popular to-day in many

countries, lead eventually to a decline in exports, for the

simple reason that in the last resort exports can only be paid

with imports.

Furthermore, money debts abroad are augmented by a

devaluation of the currency.

However, what is of crucial importance is the fact that an

abandonment of the gold standard involves the devaluation

of the entire savings of a country, particularly as invested in

savings banks, State loans, bonds, and mortgages. If the

effect of a general adjustment of prices to the fall in the value

of money is not visible at first or is deferred by artificial

devices, eventually prices always rise when a currency has

been devaluated.

Thus while the intended advantage for the export trade is

emphatically dubious and at best only of passing

importance, the loss in savings and capital is certain and

lasting.

But even if the reason for abandoning the gold standard,

as in the case of the United States, is the desire to devaluate

capital savings, - that is, if it is intended thereby to adjust the

claims of creditors to fallen prices and to the shrunken

turnover of the debtors - the success is nevertheless more

than doubtful. For what is decisive for the value of a claim is

not so much its magnitude as the business turnover of the

debtor. Everything depends therefore on increasing trade and

this is nowise assured by attacking the rights of creditors, to

say nothing of the moral and economic disorganisation

which this creates.

The heavy depletions on the capital market, the

abrogation of the rights of creditors, the menace to State

credit, and the decline in the standard of living, represent

drawbacks which ultimately outweigh the transitory

advantages.

3. Disadvantages of Foreign Exchange Legislation.

The injuriousness of foreign exchange legislation is even

more patent. Everybody agrees, and the President of the

Reichsbank, Dr. Schacht, has repeatedly expressed himself

to this effect, that foreign exchange legislation constitutes a

great evil, even though in most quarters such legislation is

considered inevitable.

Foreign exchange legislation places obstacles in the way

of settlement operations. These obstacles, in turn, hamper

trade. But every decline in trading leads necessarily to a

decline in well-being, as the latter, in our age of the division

of labour, depends on commerce. Everything therefore that

obstructs trading tends to intensify want and unemployment.

4. Inadequacy of Compensation and Clearing

Agreements.

All attempts to surmount the difficulties involved in

foreign exchange legislation have hitherto proved abortive.

This is especially true of the different forms of compensatory

trading and is evident as regards its earlier developments. It

could happen then, for instance, that an instrument

manufacturer had to accept in exchange coffee and was thus

compelled to become a produce dealer. In principle, later

developments left matters unchanged. It is the very essence

of a compensatory transaction that there is properly speaking

no money payment involved and that the goods themselves

have to fulfil this function. That is, every such transaction

represents a barter operation.

Whilst it is agreed that movements of goods (in the

broadest sense) underly all settlements, nevertheless as much

as fifteen centuries ago the Roman Emperor Justinian

explained in his Corpus Juris why barter operations are

necessarily inferior to monetary transactions. And yet the

distinguishing mark of the present-day international

compensatory trade is the abandonment of the monetary

system and the falling back on barter. It is evident that a form

of economy which the Corpus Juris deemed obsolete, must

be unequal to the task of conducting efficiently the exchange

of goods in our highly developed age. A serious effort should

therefore be made to re-instate the system of monetary

settlements in international transactions.

Similarly with so-called clearing agreements between

countries. These have now become very common, but they

cannot remove the difficulties arising from foreign exchange

legislation, for apart from the fact that in most cases, as

between Germany and Switzerland, they have led to a

considerable dislocation of trade, they are necessarily

confined to transactions between two countries, while the

realities of life demand freedom of movement in every

direction and rebel against bilateral arrangements. They lack

therefore the necessary fungibility and the attempts to

supersede the monetary system in this way have hence failed.

The League of Nations Committee for inquiring into

international clearing agreements has accordingly drawn

attention recently to their disadvantages and recommended

their abolition.

5. Need for Stable Standards of Value and for Removing

Restrictions' to Settlement Operations.

Shrinkage of international and of intra-national trade,

want and unemployment, heavy investment losses, and a

general uncertainty and loss of confidence, characterise the

present situation in most countries. It is imperative to create

once more reliable and stable standards of value and to

secure the removal of the impediments to settlement

operations between countries. The solution of these closely

related problems has become a question of life and death for

our social order.

6. Falsifying the Gold Standard through Banknotes

being Legal Tender.

Whatever the monetary system of a country, it is essential

that the measure of value should be clearly and

unequivocally determined. Thus where there is a gold

currency, a silver currency, or an index currency, the value

should be measured by gold, silver, and the index

respectively. This basis of measuring economic values, and

therefore of any monetary system, is destroyed when in the

case of a gold or silver currency the notes of the bank of issue

are made legal tender, for this compels everybody to accept

these notes in payment regardless of their real value.

Compulsory acceptance renders it even impossible to

measure the notes by the unit of value and thus to ascertain

their value within the country. Indeed, it establishes a legal

fiction on the basis of which note and unit of value are

identical. For this reason, the names of the units of value -

e.g., the terms dollar, mark, pound - become ambiguous in

that they mean now a fixed weight of gold and then the note

of a bank of issue. Accordingly, the measure of value, on the

unambiguity of which everything depends, comes to have

two definitions. This renders impossible any real

measurement and thus the whole monetary system is

falsified.

This falsification is generally hidden from the public so

long as the central bank is legally obliged to redeem its notes.

This, however, only masks the reality, since convertibility

introduces in the measurement of value an alien element.

Indeed, the fact that convertibility becomes a decisive factor,

shows how the whole problem has assumed a different

complexion.

Where convertibility is suspended, we have only a pure

paper currency, this despite strenuous legislative and

administrative efforts to keep the value of the paper at a

certain definite level, for what counts now is no longer the

value of the gold, but the question whether the note of the

central bank, measured by gold, changes its value. In fact,

the system that has been in general use since the beginning

of the World War, including the so-called gold standard or

nominal gold currencies, may be described as paper

currency.

7. Compulsory Acceptance a Relative Novelty.

Although the compulsory acceptance of banknotes

appears to-day so natural that most people cannot imagine a

means of payment not having that character, this system has

in reality only come into general use in recent times. Here are

two illustrations

Par. 2 of the German Bank Law of 1875, provided :

Payments statutorily required to be made in money need

not be accepted when tendered in banknotes and the

constituent States cannot enact such an obligation for the

State treasuries.

This provision was only replaced by its converse in 1909.

Article 3 of the Act of 1 June 1909 decreed :

The notes of the Reichsbank are legal tender.

The course of development was similar in Switzerland.

Here article 39 of the Federal Constitution of 1874 prohibited

once for all the compulsory acceptance of banknotes.

However, already in 1891 the Constitution was amended and

they became legal tender in 1914.

8. Compulsory Acceptance establishes the Dependence

of the Currency on the Central Bank.

The statutory obligation to accept the notes of the central

bank in settlement operations involves not only the

falsification of the basis of the currency. It also makes the

fate of the currency dependent on that of the central bank and

frequently on that of the banking system generally. If for any

reason the central bank can no longer redeem its notes or

maintain their parity - that is, if the market rate of the bonds

it issues falls - then, owing to the legal equivalence between

the notes of this bank and the legal standard of value, the

calculation of values generally will be prejudicially affected.

Thus it -was in the main the situation of the Bank of England,

which led in 1931 to the abandonment of the gold standard

and, similarly, it was the National Bank of Belgium that

suggested in 1935 the devaluation of the currency.

Almost a century ago Lord Overstone grasped this

interdependence when he said that if he ruined his private

bank, he would be ruined, but that if the Bank of England

committed a gross blunder, the Bank could save itself, but the

whole of the community might have to suffer grievously.

9. Compulsory Acceptance a Condition of every

Inflation.

Moreover, compulsory acceptance for banknotes forms

the legal and conceptual basis of every inflation, In the

absence of such an obligation, bank crashes, with all their dire

consequences, may occur, but never an inflation, for the

destruction of the standard of value and the falsifying of all

monetary relations, which are the mark of every inflation, can

never result from the collapse of a single bank. This

confusion is only possible when a legal equivalence has been

established between the notes of this bank and the standard of

value. It was compulsory acceptance that brought forth the

ominous slogan of the German inflation period : "One mark

is as good as another" ("Mark gleicht Mark"). History has not

known an inflation not due to the legal obligation to accept.

10. The Gold Standard as Gold for account.

If, then, the pre-conditions of an inflation are to be

eliminated and a reliable :and stable currency is to be

assured, if more especially the gold standard is to be

restored, the falsification introduced in recent decades must

be eradicated and the earlier separation between standard of

value and means of payment must be re-established. A

compulsory exchange rate excludes a stable and safe

currency. No wonder the distinguished German historian

Niebuhr stigmatised compulsory acceptance as "a legislative

provision both ridiculous and abominable" (Nachgelassene

Schriften nichtphilologischen Inhalts, 1842, p. 485 ff.)

The re-introduction of the gold standard in Germany in

October 1923, after the inflation, offers an impressive and

instructive illustration. The notes of the Reichsbank, which

were legal tender, had completely collapsed and their value

could only be stated in astronomical fractions. At long last it

was decided to introduce calculating in gold value. First,

taxes were thus calculated. Then a new institute of issue, the

Rentenbank was founded, whose accountancy basis was to

be gold units. There was, and this cannot be too strongly

insisted on, no legal obligation for the public to accept the

new notes in payment, and these notes have to this day never

been legal tender, They have therefore never been identified

with the unit of value which was then the gold mark The

system, which lasted from the passing of the inflation in the

autumn of 1923 until the introduction of the new Bank Act

in the summer of 1924 (which Act formed part of the series

of Dawes Acts), was therefore a pure system of calculating

in gold units which was not falsified by any compulsory

acceptance.

A similar example, although confined to one domain

only, is offered by China which recently adopted a gold unit

for its customs charges. By a decree of the Minister of

Finance of 15 January 1930, counting in silver in the

department of maritime customs, the most important for the

Chinese budget, was replaced by counting in gold. The basis

for these calculations in gold is a weight of 60,1866

centigrammes of fine gold and represents the customs gold

unit. This, customs unit is exclusively a calculating unit and

the decree specifically provides that the payment of duties

may, as before, be made in local means of payment, that is in

silver dollars and in banknotes. Of course, these are only

accepted in payment at the current exchange irate, this being

measured by the customs gold unit.

In conformity with the foregoing illustrations, it is

therefore suggested here to introduce generally (whilst

abrogating the statutory obligation to accept the notes of a

central bank) calculating in gold value and thus to re-

establish the conditions existing until 19,09 in Germany and

until 1914 in Switzerland.

11. Is the Inconvertibility of Notes incompatible with the

abrogation of Compulsory Acceptance ?

It ,might be objected that before the War compulsory

acceptance could be dispensed with because then, unlike

now, the notes could at any time be converted into gold. The

objection does not hold, for convertibility is not of decisive

importance, as will transpire from what follows.

12. Convertibility as a Basis of Value for Paper Means

of Payment.

It is generally believed that the value of banknotes resides

in their being convertible into metallic currency, banknotes

being considered in the main a substitute for gold or silver.

Already Adam Smith, in a famous passage in his Wealth of

Nations (bk.2, ch.2), declared that all paper money

represented only gold or silver. Similarly, the Bullion Report

of the British Parliament of 1810, which was very strongly

influenced by Ricardo, expressed itself to the same effect.

Probably not a single theory in the whole domain of political

economy has evoked such universal assent.

It is therefore natural that this view should have been

incorporated in legislative enactments. Since paper money is

regarded as a substitute for gold or silver, it must be at any

time convertible into these. Banknotes and convertibility are

therefore interdependent conceptions and hence all bank acts

the world over contain definite provisions concerning

convertibility, metallic cover, and the ratio of the notes

issued 'to the current gold reserve. Indeed, every monetary

claim is hence regarded as being in the last resort a claim for

payment in gold, although there is no necessary connection

between this and a gold standard, for a gold standard

primarily presupposes, apart from calculating in gold, that a

creditor cannot refuse acceptance of a payment in gold, i.e.,

that there is a general obligation to accept gold, but by no

means the right of a creditor to insist, in any and all

circumstances, directly or-indirectly, on being paid in gold.

Firmly based, on the one hand, as seems the general

conviction that convertibility is necessary (and practically

everywhere the ratio of the gold cover is deemed to be of the

utmost importance), there is, on the other, no doubt that to-

day most banknotes have become legally, or at least actually,

inconvertible, without thereby losing all their value. In fact,

for some notes there exist to-day no provisions of

redemption, and yet they possess value. Accordingly, there

must be, apart from convertibility, another basis for the value

of paper means of payment.

13. State Fiat as Basis of Value for Paper Means of

Payment ?

All eyes are turned towards the State to see whether, by

its fiat, it is able to confer value on valueless paper. It

becomes, however, quickly manifest that the power of the

State is strictly limited in this sphere. All large-scale

monetary devaluations known to history have referred to

means of payment the value of which rested on a State fiat.

This holds, for example, of the notes which the Scotchman

John Law issued, in France at the beginning of the eighteenth

century and even more so of the assignats of the French

Revolution. In both instances acceptance was at first not

compulsory. But presently the obligation to accept them was

decreed and soon reinforced by penalties. On 11 April 1793

the French Government prohibited the use of all metallic

money on pains of six years in chains, and in September of

the same year the decrying - that is, the verbal discrediting of

the assignats - became punishable with death and the

confiscation of property.

These drastic measures proved, however, unavailing. The

exchange value of the assignats declined steadily. At the

close of 1793 it was only 22 % and in 1795 it had fallen to

under 1%.

Not so dramatic, but not less impressive and instructive,

were the experiences during the two great American

monetary devaluations on the occasion of the war of

liberation and of the civil wars. There, too, the fiat of the

State was unable to prevent devaluation.

But by far the greatest financial catastrophe of modern

times was the German post-war inflation. It is common

knowledge that the legal obligation to accept the banknotes

of the Reichsbank could not prevent their complete collapse

and it is most significant that the notes of the Rentenbank,

which succeeded in stopping the inflation, have never been

legal tender.

Nor was it different in the case of the Austrian and was

Russian inflations. Nowhere, in fact, has the power of the its

State been able to prevent devaluation.

But this was not only the fate of weak States crushed by

defeat. France and Italy, both victors in the World War, had

to suffer heavy devaluations which annihilated more than

four-fifth of the value of their currency.

It cannot be therefore the State's fiat which confers value

on inconvertible paper money.

14. Confidence as a Basis of Value for Paper Means of

Payments ?

Not even confidence and national enthusiasm,

revolutionary determination and religious belief, can

accomplish this in the long run. One example may suffice.

When during the French Revolution in April 1793 the above-

mentioned currency law was promulgated, the whole

population of Metz assembled on the Place de la Légalité,

took a solemn oath, in the presence of the garrison, the

National Guard, and the administrative and the judiciary staff, not to draw

any distinction between the face value of the paper

money and silver. Similarly, from Toulon, where

analogous ceremonies took place, the Government

received a report stating that. the population would

carry out the law with the religious respect (

"respect religieux") due to it. at However, after a few

days the workmen at the arsenal of Toulon petitioned

that they might have their wages paid in silver, for,

they declared, "try as we may, we cannot live

otherwise". (See Marion, Histoire financière de la

France, vol. 3, p. 47, Paris, 1921.)

Even the powers of the soul cannot, therefore,

permanently confer value on paper money.

15. Acceptance by Fiscal Offices as Basis of Value for

Paper Money. The value of inconvertible paper means of

payment has a different basis, clearly revealed, in

the history of German finance. Thus during the

nineteenth century several German States issued paper

money the value of which did not lie in

its convertibility, but in that the State agreed to

accept at its

pay offices the notes it issued at their face value,

regardless

of their rate of exchange. German financial science

called

this the taxation foundation ("Steuerfundation" ).

This acceptance by the State should not be confused

with the current. obligation to accept, for under-the

regime of compulsory acceptance the taxation,offices,

following the universal custom, accept notes at their

actual and not at their nominal value. Thus the notes

of the Bank of England are worth no more at the

English fiscal offices than anywhere else. The State

accepts them at their paper value and not at the value

of the gold pound. Compulsory acceptance and taxation

foundation are therefore fundamentally different. The

basis of value of this paper money lay in that it

accepted at the fiscal offices of the issuing authority

at nominal value and, accordingly, this obligation to

accept was the important element in the wording of the

warrants. Thus the Saxon fiscal notes simply read : -

In conformity with the edict of 1 October 1818, this

will be accepted at the Royal fiscal offices,

and the Prussian money orders of 1835 and 1856 contain,

besides the value of the order, only the statement

Of full value in all payments.

Similarly in most other countries. It is true that in

many cases, as in Baden, Austria, and Wurttemberg,

there was, in addition to the obligation to accept by

the fiscal offices -that is, to the fiscal foundation-a

more or less widely current obligation to redeem the

warrants. However, here also the fiscal foundation was

of prime importance and redemption constituted only a

kind of supplementary guarantee. This is already

expressed in the order of the two undertakings on the

notes. Thus we read on the Baden paper money of 1849:

Paper money of the Grand-Duke of Baden, which all

Baden fiscal offices accept in payments at its full

nominal value i.e., as equivalent to the gross silver

money struck at the country's standard of coinage-and

is exchangeable at sight for gross silver coins at the

redemption office Carlsruhe.

Likewise, in the Reich Act concerning the issue of

Reich fiscal office notes of 3,0 April 1874, § 5, we

read :

Federal fiscal notes are accepted at their nominal

value in payments made to all fiscal offices of the

Reich and all constituent States. They are redeemable

at any time on demand for cash by the Reich's Central

Fiscal Office on the Reich's account.

In both cases therefore the fiscal foundation comes

first. It covers all fiscal offices, whilst the notes

can only be redeemed at one fiscal office.

The Wurttemberg Act of 1 July 1849 makes this relation

still plainer. Article 2, par. 1, provides:

This paper money is accepted at its nominal value in

payment at all fiscal offices of the State, as also at the tax

collecting offices. These offices are instructed to redeem

on demand this money, so far as the available funds

permit , and in amounts not under twenty gulden at a time.

Here the claim to redeem notes is conditional on means

being available. According to the clear wording of the Act,

the notes are in principle only covered by the fiscal

foundation.

Later, this principle was further developed in the

Rentenbank notes of 1923. Here no provision at all was made

for direct redemption. Apart from utilising them in

connection with public pay offices, the holder had only a

claim to convert them into annuity bonds, which fact has

played no important part in practice. Lastly, in recent years

the fiscal foundation has been most conspicuously

exemplified in the fiscal warrants of 1932, although these are

not intended to be means of payment proper. They cannot be,

either directly or indirectly, converted into ready money. Nor

can they be exchanged for securities. No redemption fund

exists nor repayments or amortisation. Their value is entirely

due to their being accepted by the fiscal offices at the

indicated value, regardless of their exchange rate.

From the Saxon pay office notes to the fiscal warrants of

the Reich, the same principle of a fiscal foundation is

evident.

16. Commercial Bills as Basis of Value for Banknotes.

The principle of the commercial bill for the Scottish

banknotes corresponds to that of the fiscal foundation for

State paper money. Whilst English banknotes have their

origin in the receipts given by the London goldsmiths for

gold deposited with them (which means that redemption is of

their essence), the Scottish notes have a different history. In

the latter case, the banks gave in exchange for commercial

bills round sums in notes of small denominations, expressing

themselves at the same time ready to accept the notes they

had thus issued, in payment at their face value for the

commercial bills they had discounted. Thus the basis of the

value of the English notes was the gold deposited, whereas

the value of the Scottish notes was based on goods sold as

expressed in commercial bills.

It is true that the Scottish banknotes were also

redeemable in precious metal, very much as was frequently

the case with the State paper money, but redemption played

an indifferent part in practice. By means of a so-called option

clause the banks frequently reserved to themselves the right

of postponing the redemption of the notes several months

after they had been presented. Thus they could wait until the

commercial bills had matured. When, on the withdrawal of

the bills, the notes flowed back, they disappeared from

circulation and the question of their redemption did not arise.

So far as the bill debtors redeemed their debts in coin or other

means of payment and not in -the notes of the bank, the bank,

without drawing on its reserves, acquired thereby the

necessary means of redeeming any floating notes.

Ultimately, in any case, the value of these notes lay in

their being accepted by the bank that had issued them.

17. Fiscal Foundation and Commercial Bill as Forms of

Clearing.

The fiscal foundation for State paper money and the

principle of the commercial bill for banknotes are therefore

basically related. In both instances acceptance by the issuer

at their nominal value, regardless of the exchange rate of the

paper, is decisive. The significance of this acceptance (or

reflux) is manifest. If, for example, the State pays an official

with such a warrant, if the official passes this warrant on to

his baker in payment for bread, and if, lastly, the baker

liquidates his tax debt with it, the baker clears his debt to the

State with the warrant that the official had passed on to him.

In the last resort we have here a clearing process, i.e., a

balancing of mutual obligations. And these settlements,

unlike in barter or in modern international compensatory

transactions, are not made without resorting to money. On

the contrary, the exchange is operated by means of a clearing

process cancelling the mutual claims through our monetary

system.

An inconvertible paper means of payment assumes

therefore a reflux. It represents, in fact, a clearing certificate

and derives its value from the exchange of economic

services. This indicates consequently the limit to issues of

unredeemable notes. Since the value of freely quoted money,

as for instance of the Reich pay notes of 1874 .or of the

Rentenbank notes, is determined by supply and demand, no

more notes may be issued than there is a demand for, that is,

than must flow back to the issuing centre. Thus in the case of

State paper money, the aggregate sum to be issued must

depend on the aggregate tax claims due or all but due. Within

this limit issues are always justifiable. If, however, this limit

is exceeded by circulating paper money representing tax

claims in the distant future, depreciation will inevitably

follow, even if the State should promise to accept the notes

at their face value in the future.

Similarly with banknotes. In principle, only short-term

obligations should be admitted as cover. The nearer the due

date of the bill, the greater is the demand for means of

payment in order to redeem it and the more assured is the

value of the banknotes issued in connection with the bill.

The more distant the due date and the less assured the payment,

the more in jeopardy are the notes having such a basis.

Rightly, therefore, many bank acts, among them that of

Germany, expressly provide that only sound commercial

bills falling due within three months at most may be

discounted by banks of issue, Indeed, experience teaches

that long-dated financial bills have hurled whole monetary

systems into the abyss.

18. Redemption or Clearing,.

There exist, accordingly, two entirely independent and

wholly different foundations whereon the value of paper

means of payment may be based : redeemability in precious

metal and clearing. There is no third possibility.

Thus all paper means of payment in every country may

be to-day actually resolved into these two elements of value.

Insofar as notes can be really exchanged for gold, their value

may be attributed to this. So far, however, as there is no

redemption and there is an inadequate metallic cover, only

clearing can confer value on the notes, and this either by

clearing against commercial bills or against fiscal claims.

Moreover, in order to extend the facilities for clearing and

thus to increase their value, many countries, at a time when

banknotes were not legal tender, introduced in addition a tax

foundation for the banknotes, statutorily obliging public pay

offices to accept them. (See, e.g., the Federal Act concerning

the Swiss National Bank of 6 October 1905, article 23.)

The difference between the two elements of value,

convertibility and clearing, which latter means here the

clearing of taxes due, is well exemplified in the Bank of

England. Here, since the Peel's Act, the note circulation is

divided into a so-called fiduciary and non-fiduciary issue.

The latter must have a 100% gold cover. It reflects the pure

idea of convertibility. The fiduciary issue however, which at

present amounts to 260 million pounds, is based exclusively,

on "an eternal debt of the English State". It is not covered by

any redemption fund. It rather embodies the idea of a fiscal

foundation.

How, then, are these two elements of value related ?

Although in the public mind the idea of convertibility

predominates, what is actually of decisive importance for the

prosperity of a country is clearing.

The idea of convertibility makes the quantity of means of

payment basically dependent on the gold reserve available at

any time. This is an entirely impracticable principle. All

attacks on the gold standard, directed against this principle,

which more especially combat the creditor's right to claim

from his debtor directly or indirectly gold, are to that extent

justified, For there is never a possibility of meeting all

liabilities by gold payments. This holds both of international

obligations and of domestic payments. It was therefore of

momentous importance and evinced profound insight, when

Milhaud in his great work, A Gold Truce, called for a

universal gold truce.

Whether a country possesses a gold reserve, depends

always more or less on chance. Accordingly, the amount of

the means of payment in circulation should never, not even

under the most orthodox. gold standard system, be

determined by the size of the gold .reserve. The economic

life of a country would have otherwise to shrink regularly

with the shrinkage of its gold reserve. In reality, the

exchange of goods remains a necessity and possible, even if

there is no gold reserve at all. On the other hand, as the cases

of France and the United States to-day show, not even the

largest gold reserve of a central bank can save a people from

widespread unemployment and poverty, whilst a monetary

system intelligently based on mutual clearing, can provide a

people with work and wealth, even in the absence of any

store of gold.

19. Examples of Clearing Money.

The diverse possibilities of issuing inconvertible means

of payment based on the idea of clearing can only be

adumbrated here.

In the first place, we may mention the inconvertible and

freely quoted State paper money described above. In most

countries to-day this is to be found in a more or less

disguised form. Besides States, local authorities may also

issue clearing notes for the imposts they are entitled to raise.

Thus in the nineteenth century Hanover city issued notes

which promoted most effectively the town's prosperity.

In the economic sphere, railways enter primarily into

account as centres for the issue of special railway clearing

notes. In Germany there is the noteworthy case of the

Leipzig-Dresden Railway founded by Friedrich List. This

Railway issued in the thirties of the last century railway

money to the amount of 500.000 thalers and this money, to

the general satisfaction, freely circulated until the

establishment of the Reich. After the World War, the German

Federal Railway also repeatedly issued its own means of

payment, most of which exhibited the character of goods

warrants, i.e., they were based on the principle of clearing.

Naturally, other undertakings, for whose goods or services

there is a general and constant demand, would also benefit by

such facilities.

The clearing principle is most particularly useful in

international settlements. Thus leading firms might issue

purchasing certificates. For instance, certificates accepted at

their face value by the I. G. Farben Company or by Siemens,

could be disposed of in London, Cape Town, and generally.

To make the certificates more widely acceptable, whole

groups of undertakings concerned with agriculture, export,

or the tourist traffic, might agree to issue purchasing

certificates jointly. Issues might also be undertaken by

special foreign trade banks, whose clients would bind

themselves to accept the certificates in payments up to a

certain amount. Lastly, work provision banks might similarly

be established to combat unemployment within countries.

For particulars on this subject, the reader is referred to the

valuable works of Milhaud and Beckerath published in 1933

and 1934.

The central banks existing at present in most

countries ought not to oppose the issue of such means

of payment. In this connection we need not examine

here whether these banks have fulfilled the hopes

placed in them or have not rather aggravated all

financial catastrophes, such as inflations and

deflations. In any case, so long as private enterprise

exists at all, mutual clearing cannot be monopolised

by a single central undertaking. The idea of a monopoly

is most closely associated with the idea of

convertibility. The issue of clearing warrants, which

neither affect the store of gold nor are able, since

they are freely quoted, to modify the average price,

cannot in principle be restricted to central banks. 1t

ought rather, within the limits drawn by the State, to

be allowed to develop freely.

20. Abrogation of Foreign Exchange Legislation.

Once it is recognised that the value of inconvertible

paper money depends on the likelihood of the issuer

clearing it, the way is open to abolish obligatory

acceptance and to re- establish the gold standard.

This, in turn, would facilitate the abrogation of

foreign exchange legislation, for this, too, is based

in the last resort on the idea of convertibility and of

obligatory acceptance.

In every country foreign exchange legislation is in

the main identical. The endless number of laws,

regulations, and principles may be reduced to the

following three aims

(a) Retention of gold;

(b) Retention of foreign means of payment (foreign

exchange proper) ; and

(c) Restriction of payments abroad.

Compared with these, all other provisions are of

secondary importance. And these three aims may be

reduced to one, namely the seizure of gold. The

retention of foreign means of payment and the

restriction of payments abroad are only means towards

attaining that one object. The foreign means of

payment are seized because they are regarded as

substitutes for gold and because it is anticipated that

by their redemption or, at least, by their being sold

on the international market, gold might be obtained in

exchange. Inversely, payments abroad are restricted as

far as possible because it is feared that through the

efflux of means of payment the gold reserve might be

drained and the maintenance of the parity be thereby

endangered. The idea that gold is not only the

standard of value but ultimately the sale and supreme

means of payment lies therefore at the root of this

type of legislation. Hence the efflux of gold and the

associated threat to the redemption fund have been

invariably the direct cause of the enacting of foreign

exchange legislation.

Here also the obligation to accept the notes of the

central bank plays a. special part. Thus whilst the

State may leave to their fate the freely quoted notes

of a private bank, without the monetary unit being

affected by the bank's exchange losses, the statutory

obligation to accept the notes of the central bank

implies that they are identified with the country's

standard of value. A loss in exchange in the case of

the latter involves therefore a modification in the

monetary basis itself. Accordingly, the State is

compelled to maintain the parity of the notes of the

central bank so long as it is bent on saving its

standard of value from fluctuations.

The identification of the monetary unit with the

notes of the central bank has, lastly, created another

source of danger which has repeatedly acted as a

decisive factor in the introduction of foreign

exchange legislation, namely its close association with

certain large-scale banks at home. Thus the collapse of

the Kreditanstalt in Austria and the Darmstadt Bank in

Germany instigated the introduction of foreign

exchange legislation in those countries. Of itself

there existed no direct connection between these banks

and the monetary standard, and the example of Sweden,

which did not rush to the aid of the collapsed Krueger

undertakings, shows that in such emergencies other

methods may be applied than those chosen by Austria

and Germany. However, where through the obligation to

accept the notes of a given bank a statutory bridge has

been built between the banking system and the national

currency, the temptation will always exist to shift the

difficulties of the banks onto the shoulders of the

currency.

All these problems assume a very different complexion

if we take inconvertible means of payment to be what

they really are, namely means of clearing in relation

to an issuer. A fundamentally inconvertible note, the

value of which lies in the issuer accepting it and

which therefore really involves no claim to payment in

gold but a claim to the services of the issuer, can

never lead to a reduction in the gold reserve. A State

paper money based on such principles could be freely

allowed to go abroad without this prejudicially

affecting the currency. It could never entail

liabilities in precious metal. On the contrary, it

would necessarily lead to goods being exported and may

be accordingly even followed by an influx of gold or

foreign exchange. What matters is that the means of

payment shall not be legal tender; in other words, that

it must be accepted by the issuer at its face value.

With this condition satisfied and the above-mentioned

limit to issues being respected, even the heaviest

losses on foreign bourses would involve no danger, for

the lower the market rate falls, the greater the

temptation, would be to acquire the warrants, inasmuch

as the issuer has to redeem them - at their nominal

value, the loss being thus converted into a gain.

Everybody therefore who has to meet his obligation with

these warrants, - in our example, the taxpayer - will

try to benefit by such falls and thereby produce a

steady demand which has the peculiarity of rising as

the market rate falls. This necessary demand provides

the floating power that imparts value to inconvertible

paper money. Such a means of payment need not dread

the throwing open of frontiers. In the words of a Swiss

writer, it will, "like a carrier pigeon", return always

to its point of departure and necessarily lead to a

demand for home products abroad, in this way furthering

the export trade.

Since such a clearing warrant has by definition a

free market rate and is therefore not linked to the

currency unit, the latter cannot be affected by any

fluctuations in the value of the former.

For clearing warrants of the type described, foreign

exchange legislation ceases to have any meaning, for

any stipulations relating to convertible money would

lose their point. In all countries, therefore, sound

clearing warrants should be freed from their fetters,

since they were only imposed on them on account of the

unsound ones, and thus at last bestow on the present

the freedom of movement denied them to-day because of

the past. That is, foreign exchange legislation should

be abrogated at least for sound warrants. Given this

first step and the basis for a new economic structure

is laid. Further progress will be thereby facilitated,

for in most countries the inconvertible notes could

be without difficulty converted into State paper money,

thus investing the present state of things in this

matter with its proper form. Should, however, one or

another central bank have transgressed the limits that

would apply to a fiscal foundation, it will not be

difficult to remedy this, without fettering a

country's general economic life by foreign exchange

legislation.

Nor can it be objected that the national economy requires

foreign exchange and can therefore not be satisfied with

clearing transactions, for, to begin with, we should remember

that probably in all countries depending on foreign exchange,

the supply of the latter has shrunk despite the most stringent

legislation and that therefore the object aimed at has not been

fully attained. But a more important point is that both

commercial and financial debts, according to firmly and

universally established views, can only be liquidated by the

goods or services of the debtor, and it is just these that are

offered by clearing warrants. It must be therefore possible to

start again payment operations on this basis. So far as the

importing of raw materials is in question, this is not

challenged. A clearing warrant, unhampered by foreign

exchange legislation and made out in gold units, is a fully

utilisable means of payment so long as there is a demand on

the world market for the goods and services of the issuing

country. If this condition is not satisfied, then foreign

exchange legislation also would be of no avail. If an

exchange of goods is actually impracticable, - that is, if the

country no longer plays a part in the world economy, - no

debt can possibly be liquidated. This holds equally of

commercial and financial debts. No one can expect that a

country possessing no gold, should pay in gold. Every

creditor should therefore recognise that a debtor can only

offer a lien on his goods and services.

Years ago the Economic Committee of the League of

Nations expressed the same idea when it said that creditor

countries must either agree that debtor countries may directly

or indirectly redeem their obligations in goods or services or

they must be resigned to not receiving any payments. The.

clearing warrants described here indicate the way in which

even heavy liabilities may be in time honestly liquidated, to

the common advantage of creditors and debtors.

Once the banknotes that had become inconvertible have

been superseded by clearing warrants, the free gold market

can be at last re-established. So soon as gold has been

divested of the property ascribed to it of. being the exclusive

means of payment and representing the core of money

claims, it becomes again a commodity like any other, Its free

movement no longer causes alarm and may therefore the

better fulfil the function of a standard of value. And this

completes the circle of our proposals, for the free gold

market which here appears as the result of -clearing, at the

same time presupposes it, since the various means of

payment can only be reliably valued when gold may be

freely moved.

It follows, lastly, that under the system above outlined

there would be no objection to gold coins being minted for

private firms and this not, as seems to be the intention at

present in France, as a form of note cover, but for immediate

circulation with a view to measuring by them at any time the

value of all other means of payment.

21. Summary.

Accordingly, we propose

1. The introduction of unambiguously determined gold

units of account as a monetary basis, e.g.

1 mark = 1/2790 kg. fine gold.

1 franc = y kg. fine gold.

1 £ = z kg. fine gold.

2. The transformation of the whole monetary system on the

basis of a gold unit of account.

3. The abolition of the statutory obligation of acceptance for

the notes of the central banks.

4. The removal of the monopoly of the central banks and its

replacement by general regulations concerning the issue

of means of payment.

5. The abrogation of foreign exchange legislation and the

re-establishment of a free gold market.

6. The unrestricted right to mint gold coins.

22. The Practical Realisation of the Proposals.

a) Through international agreements.

Everybody is agreed that something should be done to

remove the monetary chaos and the obstacles to settlement

operations. Here also hope is commonly centred in

international conferences. However, the value of such

conferences for the solution of economic problems is not

great. Think in this connection of the World Economic

Conference of 1933. This was eagerly looked forward to by

all peoples and yet, notwithstanding careful preparation,

produced virtually no practical results.

However, even if within the near future a monetary

conference could be arranged to meet and if, moreover, full

agreement could be reached among the participating States,

the effect would be at best to re-establish the parity between

the monetary units and to impose an unconditional obligation

on the parties not to modify deliberately this parity nor to

change it without the consent of the other contracting parties.

But that would only dispose of a comparatively small part of

the present difficulties, for only most rarely - as in the United

States recently - has the abandonment of the gold standard

been an arbitrary act. In by far the majority of instances, the

gold standard was most reluctantly dropped. Heavy calls on

credit institutes, excessive claims on the central bank, a

rising efflux of gold, and, finally, the threatening

impossibility, despite all efforts, of maintaining the parity of

the banknotes, were for the most part the really decisive

factors in the abandonment of the gold standard. For such

cases an international agreement on monetary parities would

offer no solution.

So long as the principle of central banks is retained and

their notes, being made legal tender, are identified with the

standard of value, no international agreement will be able to

prevent the recurrence of present-day conditions , for under

this system the collapse of a single leading bank, to say

nothing of the collapse of the State finances, may render

impossible the maintenance of parity. However, even if, to

meet such cases, the several countries concluded a

convention providing that the gold reserves of the diverse

central banks should be automatically mobilised to save the

currency of a country in need, a scarcely credible sup-

position, even this would be insufficient in hard cases, for the

magnitude of the monetary obligations maturing at any given

moment would probably always exceed the quantity of

available gold.

It also remains a moot point how the problem of foreign

exchange legislation could be settled at such a conference,

seeing that the granting of loans, useful as these would be to

those immediately concerned, in no way solves the problem.

And yet without this, even a fresh determination of parities

would prove unsatisfactory. On the contrary, the object

should be to rebuild on a sound basis the entire system of

international payment arrangements,

b) Through intra-State legislation.

From what precedes follows the possibility that each

several State, having made up its mind, may, by abolishing

the obligation to accept and recognising the reflux principle,

re-establish for itself the gold standard and rescind its foreign

exchange legislation. This may seem fantastic. But the reader

should remember the German inflation period. Then, too, an

escape without external assistance appeared impossible.

"The hole in the West", speculation on foreign bourses, and

similar obstacles, which Germans could not control, were

quite generally regarded as the causes of the depreciation of

the mark. Eventually, when things were at their worst, when

in some parts of the Reich serious disorders had broken out,

and when external help was out of the question, the country

succeeded, by its own efforts, without the aid of any foreign

Government, without an international conference or

convention, to stabilise the mark, to safeguard it against all

foreign speculation, and even after a few months to abrogate

the foreign exchange legislation then in force. To-day, as at

that time, the free resolve of any country may determine the

fate of its currency. The country that first finds the way out,

that removes insecurity, and at the same time re-establishes

the freedom of monetary operations, will march well ahead

of the other countries. It may even be assumed that a mighty

stream of capital for long-term investment will pour into it

from all sides.

c) Through private initiative.

Even if, however, no State were for the moment ready to

proceed along this line, there remains the possibility of

finding a way out of the monetary chaos through private

initiative or at least to prepare the way for this. When in the

eighteenth century the national monetary units, because of

alleged State needs, continually fluctuated and when it was

therefore impossible to rely on the value of currencies for a

measurable time even, Hamburg merchants, more

particularly, discovered a way out. By founding the famous

Hamburger Girobank, they, following the centuries' old

Chinese Tael system, made themselves independent of the

debased State coinage by adopting as the basis of all their

accounts an unminted definite weight of silver in the place of

State money. This weight, called Mark Banko, constituted an

unchangeable unit of calculation,. which came to be of the

greatest service economically for the whole of Northern

Europe.

There can be no doubt that the application of the same

principle, with gold instead of silver as the basis naturally,

might exercise a similarly far-reaching influence to-day. Just

imagine that before the devaluation of the Belgian franc, a

Belgian undertaking of good repute had declared itself ready

to take up a long-term loan at its actual gold value, regardless

of the exchange rate of the franc. The crowd of would-be

investors would probably have broken through all barriers.

In this connection the proposed private calculation in

gold should on no account be linked with the national

monetary system. Accordingly, I do not suggest here the

appending of gold clauses (gold dollar, gold pound, or gold

franc) to a country's currency unit, for experience teaches

that such clauses - which hold permanently before the

statutory means of payment its ideal as in a mirror - only

rarely survive the fate of the national currency. Thus in

Belgium, when the franc was devaluated, the gold clauses

were revoked and only contracts in foreign currencies were

left untouched. Private calculation in gold, like the erstwhile

Mark Banko system, should be independent of the national

currency. It should be therefore based on a separate unit, for

which a simple calculation in grammes of fine gold suggests

itself here. This, would also serve as a basis for an

international calculating unit, which has. been widely

desiderated for many decades.

All that would be demanded of the State is not to prohibit

calculating in gold. The State could never suffer through this,

for even if a Government should deem it expedient to

devaluate the national currency, as was frequently the case

already in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there can

be no ground for imposing a devaluated currency unit on

those who had freely agreed to use for their economic

transactions among themselves another and constant value

basis. Investors in all countries would joyfully welcome such

a solution and there are not a few undertakings which, under

these conditions, would be decidedly ready to place long-

term loans at moderate interest rates. Once it is

demonstrated, however, that the monetary chaos, which

seems to most men the work of an inscrutable fate, may be

overcome, the profoundly beneficent effects of this for the

peoples of the world will not fail to become apparent.

(Translated by G.Spiller, London.)

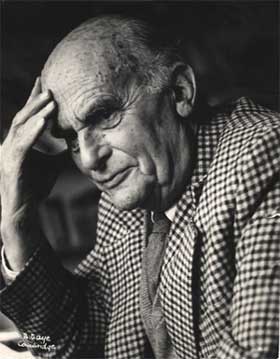

Walter Zander (born June 8, 1898 in Erfurt, died April 7, 1993 in South Croydon) was a German-British lawyer, scholar and writer. He was Secretary of the British Friends of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem 1944-71, Governor of the University 1972-93, Senior Associate Fellow at St Antony's College, Oxford 1971-88 and author of several books and articles, many of them about Israel and its international relations.

The son of a prominent Erfurt lawyer, he studied at the Gymnasium, before being called up for military service in 1916. During World War I, he served as a non-commissioned officer in the German Army and was awarded the Iron Cross. After the war, he went on to study law, philosophy and economics in Jena and Berlin. After a brief period as an assistant to one of the leading lawyers in Berlin, he set up his own practice in the city. In 1929, he took a one year leave from his practice to study economics at the London School of Economics and the Sorbonne University.

He married Gretl Magnus in Berlin in 1931, and they had three sons and a daughter, among them legal scholar Michael Zander and conductor Benjamin Zander.

No comments:

Post a Comment